Could sand spread on sea ice help keep the Arctic cool?

A bold plan aims to preserve young ice — and halt the loss of multiyear ice.

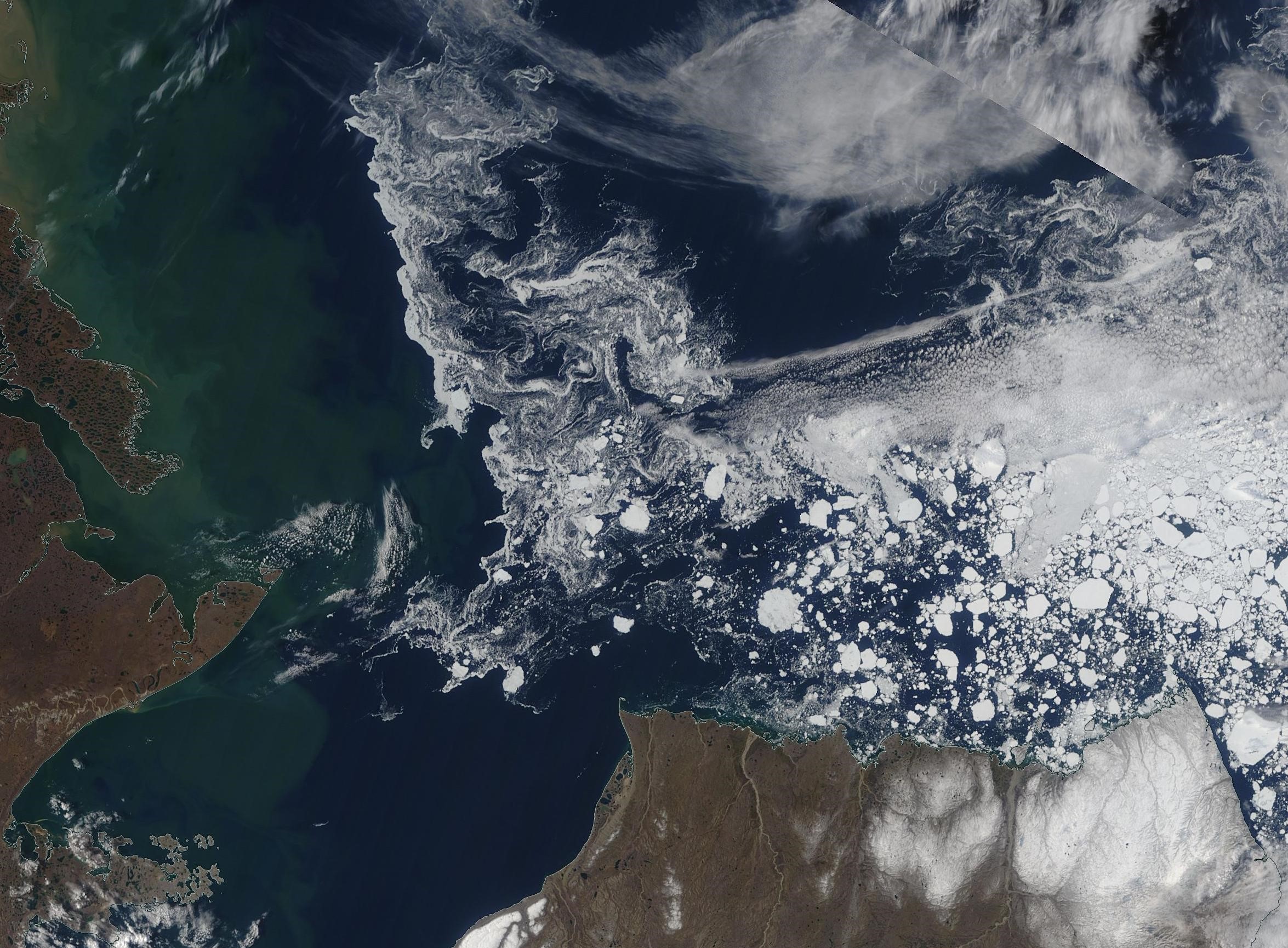

Think of the sea ice of the Arctic Ocean as a reflective heat shield vital to a stable climate.

Then consider that about 95 percent of multiyear ice, the older ice that’s crucial to this heat shield, has vanished in the last four decades.

This worries climatologists and scientists the world over, who recognize the role that the Arctic plays for the planet.

One question that’s begun to gain some attention is whether the reflective capacity of Arctic ice could be enhanced by spreading a thin layer of white sand on a portion of the ocean in the spring.

The plan to spread sand, promoted by a nonprofit group called Ice911, drew a high-profile plug in the New York Times recently, when U.S. climate policy activists Durwood Zaelke and Paul Bledsoe said it is one step that deserves immediate attention.

“We should start field testing this strategy immediately. The risk of losing the Arctic’s stabilizing function for the global climate now appears far greater than the risk of experimenting with geoengineering. Save the Arctic, and we’ll have a chance to save the climate,” they wrote.

The sand would reflect more summer light, the way wearing a white shirt in the summer helps keep a person cool, according to the theory.

Leslie Field, the chemical and electrical engineer who founded Ice911, said she began focusing on this more than a dozen years ago, worried about what future her own children would face if nothing is done to change the course of history.

“For 700,000 years, over the entire course of human evolution, our Arctic Ocean’s sea ice shield has reflected most of the summertime sun, keeping the northern ocean cool and the northern air cold,” Field told the Arctic Circle Assembly in October.

But warming in recent decades has transformed the region so that most of the multiyear ice is gone.

“There’s no natural way, under current conditions, that multiyear ice is going to come back to the Arctic,” she said. “It’s an alarming thing.”

While melting ice was once primarily a consequence of rising temperatures, it has become a driver of climate change.

“This is because with the loss of reflective ice in the Arctic, we no longer reflect nearly as much solar energy in the summer, but instead we’re absorbing it into a warming ocean, into melting the ice that is left, in an accelerating backloop.”

Open water reflects about 5 percent to the sun’s energy, which multiyear ice reflects up to 70 percent, she said.

Adding a thin layer of sand to young ice could increase its reflective power to 45 percent from 35 percent, she said.

The idea needs to be tested, she said, but it holds promise and should be pursued.

“Saving Arctic sea ice appears to be the task that humanity must take on first to stop the acceleration of warming and instability, to give the world time to adopt the rest of the measures needed to stabilize climate, such as decarbonizing our economy and atmosphere,” she said.

Field told the BBC that covering 100,000 square kilometers of ice, less than 1 percent of the Arctic Ocean, might cost a few billion dollars per year.

The sand would be spread from icebreakers, sprayed onto the ice in the spring. Tests so far show that the process works on lake ice and that the sand is safe for fish and birds.

Practical questions include whether the application by icebreakers would lead to greater loss of ice and carbon emissions and whether winds would make an even dispersal of sand impossible.

For Field, the answer is to keep trying.

Dermot Cole can be reached at [email protected].